Interview with Benjamin Wood

“The only thing about your work that you can control is the work itself. How the world receives your work is entirely at the discretion of the world. Focus all your efforts on the only thing that matters. (This is advice I have to give myself repeatedly, so, fair warning, its efficacy is questionable.)”

The Young Accomplice, published June 2022.

Benjamin Wood is the author of four novels. His debut, The Bellwether Revivals (2012), was shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award and the Commonwealth Book Prize. The Ecliptic (2015) was shortlisted for the Encore Award and the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award. A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better (2018) was shortlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger Award and the European Union Prize for Literature. His latest novel, The Young Accomplice, will be published by Penguin Viking in June 2022. He is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at King’s College, London, where he founded the PhD in Creative Writing programme.

James Baldwin says that “Every writer has only one story to tell,” yet each of your novels seems very distinct in subject matter and style. What would you identify as consistent themes and hallmarks of your writing?

Well, I try not to write the same book twice if I can help it, but I guess there’s an obvious bridge that connects the novels I’ve published so far. They’re concerned with the lives of creative people (architects in The Young Accomplice, a painter in The Ecliptic), or else they tell the stories of outsiders who are in thrall to creative people (a troubled musician in The Bellwether Revivals, a thwarted set designer in A Station on the Path…). I find people’s capacity for creativity to be one of the most interesting and meaningful things about the world, so I’m drawn to exploring that in my work.

Which of your novels is your favourite, and why?

The only good answer to this question is: the next one. But A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better seems to be the book I recommend to people most, when they ask me: ‘Which of yours should I read first, then?’ I think that’s probably because it’s the easiest one to describe succinctly.

Which of your novels has been the hardest to write?

None of them has been a pleasant sail into the sunset. I’ve always written alongside my teaching commitments and those responsibilities tend to multiply at the most stressful stage of writing a book. But The Young Accomplice was absolutely the toughest novel to complete, just from a logistical standpoint. I wrote the bulk of it while shielding at home during the pandemic with my wife and kids. And, for those twelve months or so, my sons were banging on my door wanting me to play with them, or my heart was heavy with the awareness they were in the room next door, growing up without me, as I researched some arcane fact about tractor maintenance in the 1950s. Because of the period it’s set in, and the various facets of the book I needed to know about (small farm management, running an architectural practice, Frank Lloyd Wright, the borstal system, etc.) The Young Accomplice took an ungodly amount of research, too. And the more research I need, the slower the writing tends to go.

In a previous interview you mentioned that you write songs when you are stuck on a novel. Do you still do this? Do you have any other strategies for working your way through a tricky patch?

Yes, I’ve been writing a lot of songs recently, in fact. The process isn’t the same as fiction writing: it challenges me in different ways. Sitting with a guitar or at a piano, trying to draw out a chord sequence, a vocal melody, an arrangement—there’s something uniquely therapeutic about that as a creative practice. It’s more directly emotional, and it unclogs the U-bend of my brain. Writing a song is often the only way for me to understand how I truly think or feel about something, or someone. And it’s more overtly autobiographical than my fiction.

Do you have a complete plan for the novel before you start to write?

I do a lot of thinking about the arc of the story before I begin—who the characters are at the beginning, who they will become by the end—but I never have a rigid plan. Instead, I do the plot-making equivalent of looking up the journey on the map before I set off, noting where all the important junctions and turn-offs are, then putting the map in the glovebox; and if I happen to encounter a more direct or scenic route along the way, or if any landmarks I thought I would stop and see get bypassed, then I don’t worry too much about it—as long as the journey is interesting and I reach my intended destination. Then I go back and delete all the tiresome road travel metaphors I’ve put in.

How many drafts do you write?

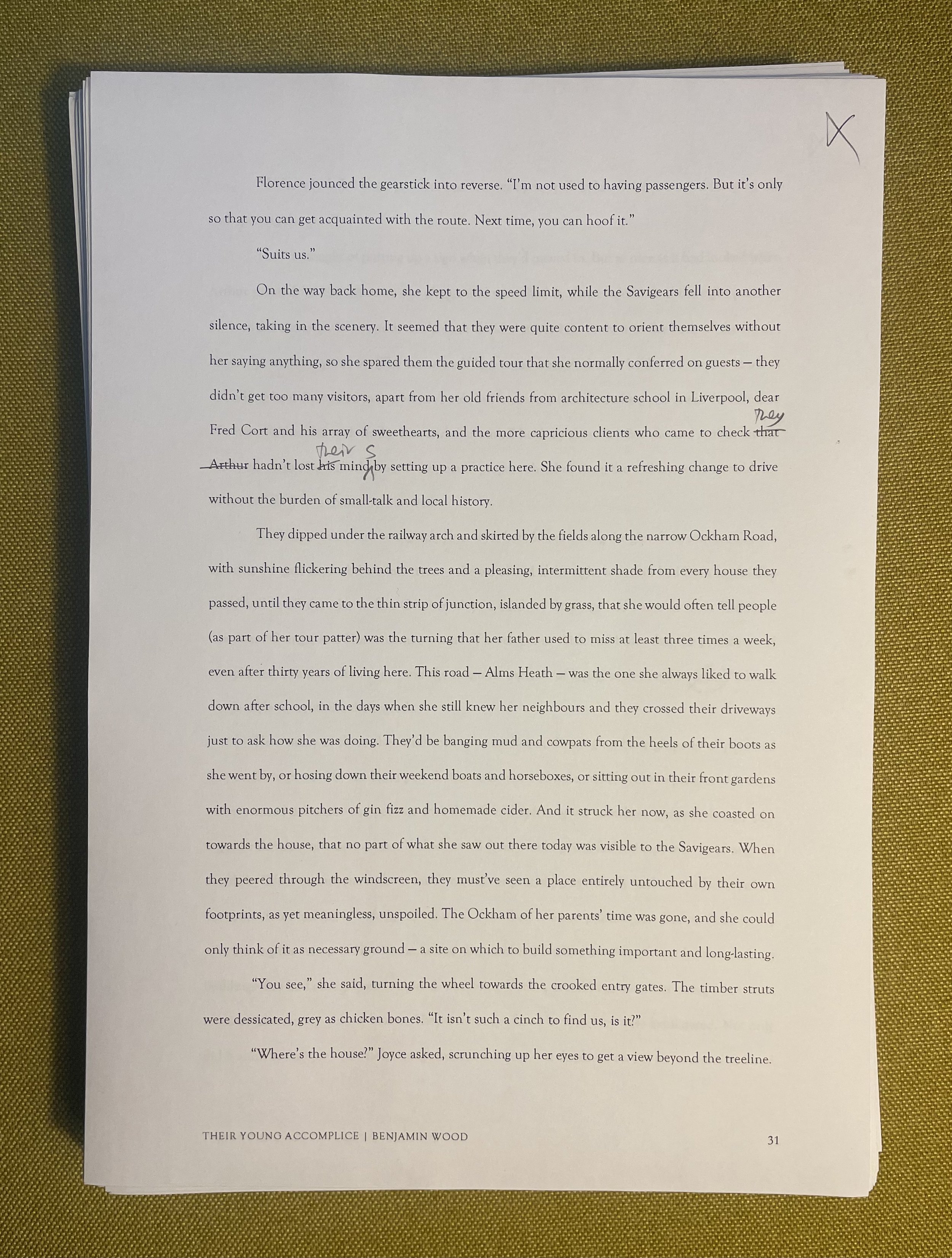

It really depends what you mean by ‘drafts’ here, because, as I see it, the novel is in a constant state of redrafting—I write the first sentence, and keep re-writing it until it convinces me to let it take up residence. Then I move on to the next sentence. That’s always been my process. I save a version of the document every day and date it, so I have a record of its progress. My editor will get a version of the novel that’s as close as possible to the finished article. Then I’ll usually do one (sometimes two) more drafts, taking on board the feedback. I tend to do a lot of ruthless cutting and some repositioning of backstory at this stage. Then the copyeditor gets his or her hands on it, and I do some additional minor tweaking in light of the problems that might be thrown up.

Do you find it easier to write a first draft, or revise it?

See above. The first draft is nothing but torment. I am a born tinkerer.

Image of The Young Accomplice manuscript: “The first draft is nothing but torment. I am a born tinkerer.”

Do you set yourself a daily word limit?

I used to, then my kids were born! As a freewheelin’ twenty-something devoid of responsibilities, 1000 words a day was always the target I set myself, and I’d be annoyed if I didn’t reach it—because, come on, what else did I have to do all day? But now I’m elated if I can write 250 good words in the time I have available. Experience has taught me that it’s better to write nothing at all than write 1000 words I’m embarrassed by the morning after. One or two short bursts of clear-sighted productivity per day: that’s the dragon I chase now.

Etgar Keret recounted how he would attempt to re-draft novels even after publication (a habit curtailed by a friend chucking all his new revisions out of the window of his office). Have you ever re-read one of your novels after publication and wanted to change anything? If so, what?

All books are a product of the circumstances in which they were written, and I couldn’t have poured any more of myself into them at the time or got them out of my head with any greater efficiency. There are many, many passages in my first novel I’d like to take back and revise, but I wrote those passages when I was twenty-six, and that book was shaped by the viewpoint of the twenty-six-year-old me. I’m comfortable with the idea that when a novel is published it’s no longer an entity I’m in charge of creating. Still, I wish I could’ve retained the original title I had for A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better, which was much shorter and easier for people to repeat.

You founded the Creative Writing PhD programme at King’s College London; why did you do this?

I ask myself the same question every day, Sally! I suppose it was built from the experiences I’d had as an MFA creative writing student in Canada, and from teaching creative writing at UK universities for so long. It had always struck me that the project a student completes during their Master’s is rarely the book that launches their writing career—it’s usually the thing they write next that’s the most significant work they produce. For that reason, many very talented writers slip through the net at that crucial stage, because of financial pressures or because they don’t have the support and guidance they need to continue with their next idea. The opportunity arose at King’s to develop a new programme at postgraduate level, and I proposed that we could provide for students who are in that vital in-between phase of their writing lives, to help them complete a book-length project and prepare them for the challenges of a writing career at the same time.

We’ve discussed before – briefly – the idea that being a creative writing professor is similar, in some ways, to being a shrink. Do you agree with this, and in what ways?

Well, I’m not a qualified psychiatrist and haven’t ever masqueraded as one, but I’d imagine there’s some crossover. The creative writing teacher’s role involves listening acutely (and regularly) without judgment, helping the writer become more aware of their own strengths, giving them solutions to overcome unwanted habits, and steering them towards a better understanding of their own decision-making. There’s a lot more money in psychiatry, though, and better furniture.

Who do you turn to for criticism of your writing?

Amazon reviewers—they’re very forthcoming. Before a book is published, though, I’ll seek the opinion of my agent, Judith Murray, who’s a really astute reader and understands instinctively what my work is trying to do. My editor at Viking, Mary Mount, points out all the weakest beams in the framework of the story right away, and that’s invaluable. My former editor at Penguin Press in the USA, Ed Park, gives solid gold editorial feedback—I’d listen to anything he tells me. And my wife’s very good at spotting all the moments in a book I’m most unsure about and telling me if they work or not, so I value her opinion a great deal.

You have young children; how has the experience of being a father changed your work?

In every possible way. Not just from the standpoint of having fewer hours in the day to write, or read, or sleep. Having children has changed my perspective on the world. Everything I do is in the context of what they see, and everything I write is in the context of what they might one day read. And I’d like to think it’s possible to be a good father and a good novelist, but if I fail at the latter in pursuit of the former, so be it.

Hemingway stood up when he wrote; how do you write? Do you have any necessary prerequisites?

I’d guess that Hemingway stood up to write because he’d have passed out drunk in his chair otherwise. It obviously worked for him. I used to be very, very fussy about the conditions I needed for writing—a perfectly organized tabletop, the right amount of natural light, etc—but now my only requirements are a pot of coffee and a relative amount of quiet.

Who are the living writers that you admire?

Oh, it’s so much easier—and fairer—to list the dead ones... Among the living: Marilynne Robinson (Home is an absolute masterwork, in my opinion), Paul Auster, Graham Swift, Tobias Wolff, Kazuo Ishiguro, Claire Keegan, ZZ Packer, Atticus Lish, Sarah Hall, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Sarah Waters, Jennifer Egan, Samantha Harvey, Sarah Moss, Andrew O’Hagan, Hilary Mantel, Asali Solomon, James McBride, Eleanor Catton, Michael Chabon, Peter Carey, Annie Proulx, Cormac McCarthy, Maylis de Kerangal, Ron Hansen, Ned Beauman, David Whitehouse, Emily St John Mandel, Joshua Ferris, Nicole Krauss, Michel Faber, Helen DeWitt, Madeleine Thien, Aaron Sorkin. And a catalogue of others I’ve embarrassingly failed to mention here.

Besides THE YOUNG ACCOMPLICE, which book should I rush out and buy immediately?

The Big Rock Candy Mountain by Wallace Stegner.

What advice would you give to another writer?

The only thing about your work that you can control is the work itself. How the world receives your work is entirely at the discretion of the world. Focus all your efforts on the only thing that matters. (This is advice I have to give myself repeatedly, so, fair warning, its efficacy is questionable.)